The United States was celebrating its bicentennial in the summer of 1976. Joining in the patriotic spirit, Zena completed her portrait to honor Chuck Hall, the recently deceased fifty-six-year-old mayor of Miami Beach, first mayor of Dade County, and former political rising star. The revered mayor’s bust awaited dedication to the people of the city in a public ceremony. Even so, Zena was faced with a dilemma.

Her first posthumous portrait in clay, a greater challenge than working from a live model, had required the use of still photographs she had obtained. She had supervised the casting of the clay sculpture into plaster and the plaster version into bronze at a New York art foundry. She had chosen a marble base, a pedestal and had a plaque inscribed. Despite repeated inquiries, she hadn’t been compensated because of insufficient fundraising. The date of unveiling was approaching. Dignitaries, including entertainer Bob Hope and the venerable Senator Claude Pepper, were invited to speak.

Standing Up

Zena agonized, mulling things over. She had done her part, but if she delivered the bronze, she might never be paid. Zena, a fighter for other causes, was realizing that the time had come to stand up for artists like herself.

Chuck Hall with Silver Rolls Royce, 1964

Zena had known Chuck Hall personally and was committed to portray him before his unexpected death in 1974. The good-natured and silver-haired mayor, an art enthusiast, was respected. He had been the seaside mecca’s glamorous ambassador, often cruising its tropical tree-lined byways in his silver Rolls Royce. Having hosted both the Democratic and Republican National Conventions only two years earlier, he not only warmed the hearts of his constituents, but also expanded the city’s popularity.

Dade County Mayor Chuck Hall [left] meeting with Governor of Florida Askew, Florida Memory, May 1972

To the flocking tourists and “snowbirds,” Miami Beach, a natural barrier island with manmade islets, was America’s “playground.” To its permanent population, it had the feel of a small town with a unique flair. Alongside the sun worshippers, gangster elements and glitterati, ordinary residents, transplanted from the Northeast and Midwest for the warm healthful climate, were bringing their desires and talents and gaining a toehold. Remaining home to retirees and an aging Jewish population, the area was experiencing an influx of multi-national immigrants and a broadening base.

Zena was a pioneer within the growing cultural community of Miami Beach and South Florida since the 1940s. She taught art therapy to war veterans in the convalescent hotels when she first arrived and was art director at the “Y”. She continued to offer educational public lecture-demonstrations, during which she would fashion a portrait in clay before a live audience, and soon established her own working and teaching studio.

Zena was glad to accept the offer from Jeanne Levey, a formidable fundraiser and philanthropist, to produce a bust of Mayor Hall for the people of Miami Beach. Mrs. Levey, founder of Miami’s National Parkinson’s Foundation, who had known Zena from the rendering of her dying husband’s portrait years before, would spearhead the fundraising campaign.

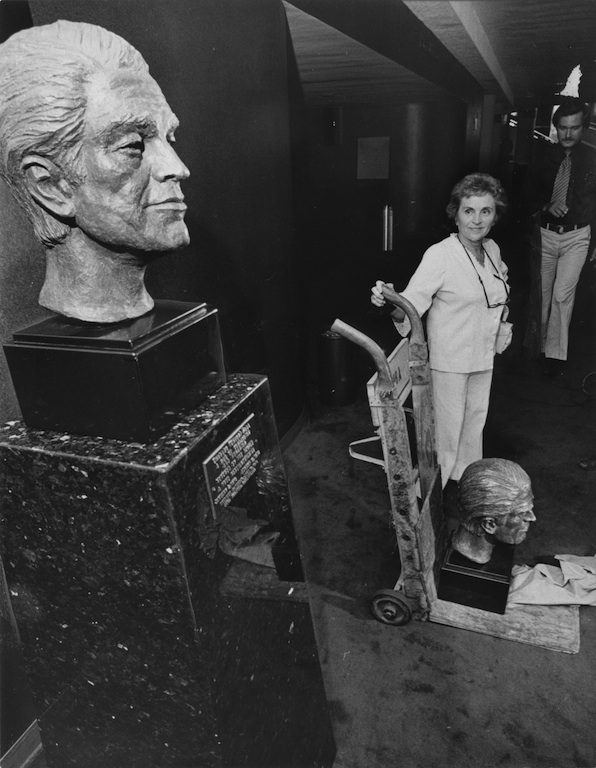

Zena made a painful decision the day prior to the ceremony as she delivered the pedestal: to present the patinated plaster in lieu of the bronze. When she was paid for her efforts, she would replace it. She steeled herself for her announcement, not predicting its outcome. Senator Pepper grew pale. Mrs. Levey was shocked. People in the audience approached Zena, offering to contribute. The incident made international news and caused a firestorm of public controversy that incriminated all sides. Zena’s daring move not only brought sympathy from people like Eileen Bohland, but also sharp criticism.

A Sad Affair

Outspoken newspaper editor-publisher Paul Bruun took on the fundraising, boosting the campaign by publishing incoming contributions in the Daily Sun-Reporter. Zena settled on less than the original commission in order to conclude the matter. When the summer was over, the permanent bronze had taken its agreed upon place in the lobby of the Theater for the Performing Arts, recently improved as the late mayor had envisioned.

September 11, 1976, Miami Herald, Joe Rimkus, Jr.

After the city leased their auditorium in 2007, however, the portrait was removed, leaving its whereabouts unknown. As Miami Beach’s 2015 Centennial approaches, the mayor and the artist merit remembering. The Chuck Hall sculpture deserves placement once again near the stage.