Everyone has a mother, and nearly everyone has understood the maternal relationship by having known or been one. While this is patently obvious, to Zena Motherhood would become her strength. The theme of Motherhood–evocative of caring, filled with gratification and laden with self-sacrifice—reverberated throughout her career. She sketched her own mother, sculpted her and had the portrait cast in bronze.

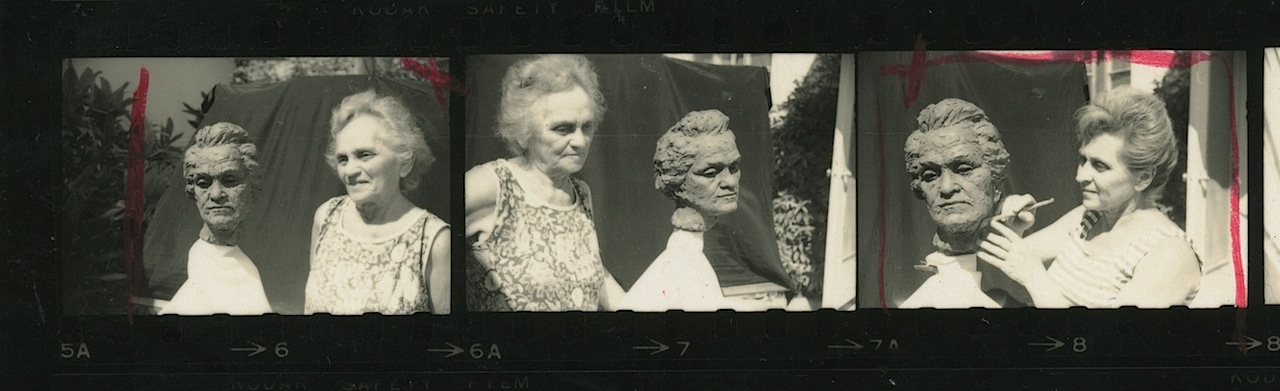

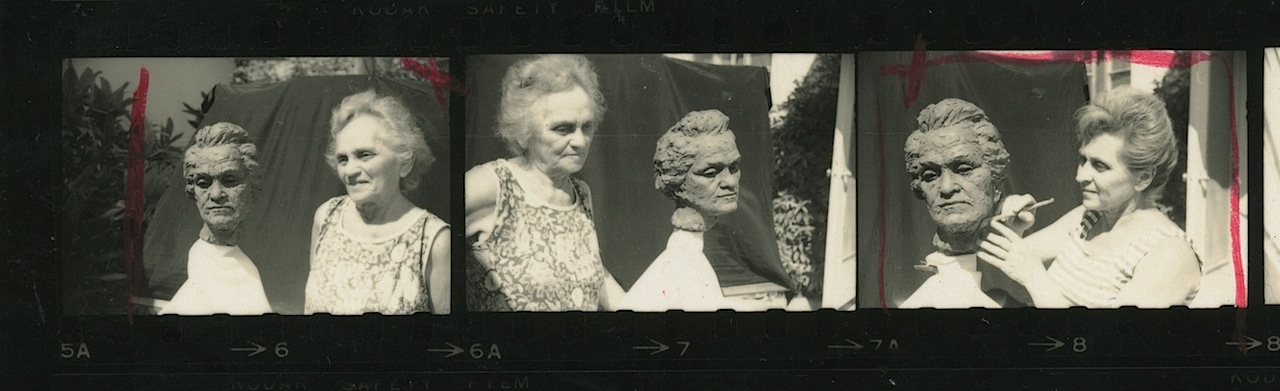

Zena with bronze of Manya Goldin, 1969

To financially support herself and her child, Zena eagerly took on commissions from sons who also wanted portraits of their mothers. Zena’s sculpture of her own mother gained new life during exhibition. She gave it the iconic title, “A Mother for Peace,” in the Artists Speak for Peace shows she organized.

The Motherland

Zena’s earliest memories of her mother coincided with emigration from Mother Russia when she was four years old. To travel to America during World War I necessitated crossing Asia to avoid war-torn Europe. Zena recalled feeling hungry on the ship from Japan and how her mother allowed her and her sister to eat rice leftovers in other peoples’ bowls. Her mother Manya was normally protective, but generous, strong in her convictions and unafraid.

In “Refugees,” Zena focused on the journey of a mother holding onto her child while shouldering a sack of meager belongings. Experimenting with the subject in stone, soap, and clay, she captured the mother’s burden together with the anguish of the child. The subject of mother and child became an opportunity to convey the cruelty of displacement.

Refugees, limestone, 1940, The Wolfsonian-FIU, Miami Beach, FL.

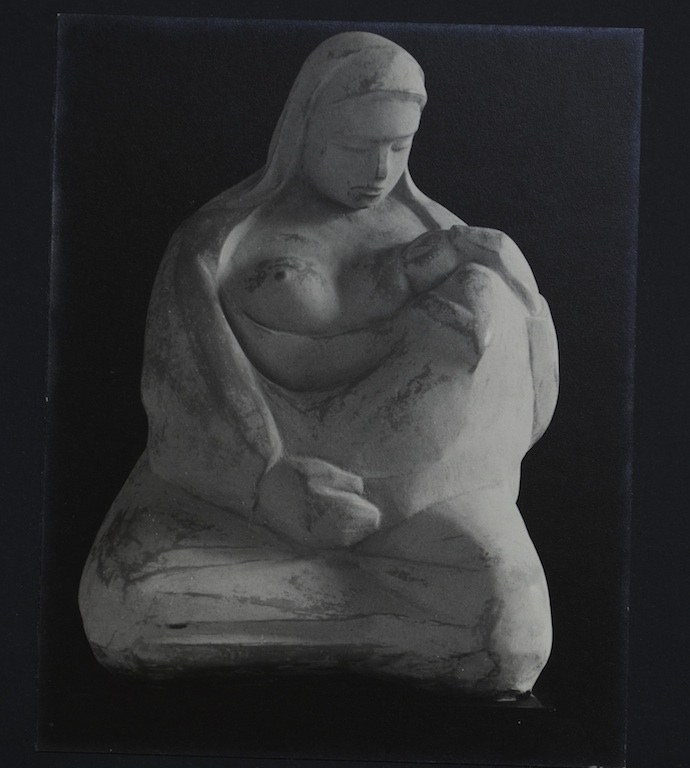

Zena took on the classical symbolism of Motherhood in “Mexican Madonna.” She is a hefty figure nursing her child, constructed using the coil method and originally finished in matte-glazed ceramic. The solid spreading form projects anchoring and stability. This work followed Zena’s 4-month Pennsylvania Academy traveling fellowship to the Southwest and Mexico just before the United States entered World War II. Despite the hardship of that period, the discovery of new places and people with fellow students and her future husband Felix was “a glorious time.”

Mexican Madonna, ceramic, 1942

Zena was introduced to Felix through a mutual friend on a bitter cold evening in the winter of 1940. She and her new roommate were headed to their new Philadelphia apartment to settle in. Much later Zena wrote in a memoir how she was “impressed with Felix’s personality – his interest in what he was doing, his deftness and neatness“ the night they met as he helped her unpack. Their attraction was strong, though she could not yet have anticipated that he would be the father of her only child.

Zena became a mother in her mid-thirties eager for its responsibilities and pleasures. The concerns of being a mother, a caregiver to her parents and eventually, a grandmother competed with the artist in Zena. Yet, the first calls to motherhood inspired loving drawings and intimate, playful clay sketches. Over a lifetime, her daughter would be a continuing model for artwork and an incomparable reward.

Zena in studio, sculpting daughter Verna, 1952

I literally grew up in my mother’s studio. I remember always having “to pose” for her. She tried teaching me to sculpt in clay, to paint with oils, but I had no talent in comparison to her. My parents were separated during the war, and they never lived together after my father’s discharge at the end. Living with my maternal grandparents, Mother and I were very close, somewhat like sisters. We would arrange paintings together on the walls of our small living room, and I would organize her studio papers at tax time. During college, I studied history and discovered the talent I had for seeing. I became an art curator. --Verna Posever Curtis

For My Mother

I’ve written these stories about my mother as a tribute to her 55-year career as a pioneer artist and activist in South Florida. She held strong principles for peace and justice during a long life, and she inspired my career.